|

When US Presidential

Press Secretary Robert Gibbs

lost his temper this past week, railing against his boss’s

left-leaning critics and saying, among other things, “They will

be satisfied when we have Canadian healthcare,” it was a burn

felt across the nation. Those same critics fired back and

suggested Gibbs take a permanent vacation. This prompted the

Press Secretary to apologize and promise to play nice from now

on.

What I did not

notice in the backlash were very many of those critics saying,

“Hell yes, we want Canadian healthcare!” A few probably did, and

if I tried harder I could probably find them, but that wasn’t

the message percolating to the top of the news cycle. My guess

is that our problems (waiting times, doctor shortages) are as

well known to them as their problems (soaring costs, the

uninsured) are to us. Large segments of the populations on both

sides of the border seem perfectly happy to play up this false

dichotomy, when in fact, there exists an option that would trump

both systems handily: an actual free market in health care.

Of course, many people

fail to realize that the American healthcare “market” has been

hamstrung by an ever-growing tangle of regulations for three

quarters of a century now. But beyond this, there is a

widespread notion that must be combated, especially here in

Canada, before a truly free market in health care could ever

again become palatable to anything more than the libertarian

fringe: the notion that it is wrong to profit from the misery of

others.

This idea was on display

in reactions to the

CMA’s latest policy document, released in anticipation of

the group’s annual meeting next week. While very tame by

libertarian standards, the document’s recommendations

nonetheless elicited strong opposition. Len Rose, Executive

Councillor of the B.C. Nurses’ Union, argues

in a letter to The Vancouver Sun that “Canadians know

that profit-driven health care vacuums up huge sums of money

from taxpayers and deposits these in the vaults of corporate

executives and shareholders,” and worries that “amputating more

of our public system and turning it over to profiteers will give

Canadians fewer services at a higher cost.” Drs. Danielle Martin

and Irfan Dhalla of the group Canadian Doctors for Medicare,

while applauding the CMA’s

shift away from privatization, nonetheless find fault

in some proposals that will “result in a massive transfer of

wealth away from individuals and governments toward insurance

companies.” They worry that due to such remaining vestiges of

formerly more aggressive privatization proposals, “we will end

up paying more for the same services.”

While couched in practical terms of cost and efficiency,

quotations like these are dripping with condemnation of

corporate executives, shareholders, insurance companies, and

other “profiteers.” In order to defuse some of this antagonism

toward profit in medicine, it is necessary to examine what,

exactly, profit is. Without getting too technical, profit can be

understood as total revenues minus total costs.

This represents the return successful business owners receive

for running a business. Unsuccessful business owners receive

losses (or in a mixed economy, subsidies). Alternately, profit

can refer to the return to investors who lend money to a

business, but then, these investors are not so different from

shareholders, who are another kind of owner. (And if loans are

not repaid, investors can become actual owners, too.)

While couched in practical terms of cost and efficiency,

quotations like these are dripping with condemnation of

corporate executives, shareholders, insurance companies, and

other “profiteers.” In order to defuse some of this antagonism

toward profit in medicine, it is necessary to examine what,

exactly, profit is. Without getting too technical, profit can be

understood as total revenues minus total costs.

This represents the return successful business owners receive

for running a business. Unsuccessful business owners receive

losses (or in a mixed economy, subsidies). Alternately, profit

can refer to the return to investors who lend money to a

business, but then, these investors are not so different from

shareholders, who are another kind of owner. (And if loans are

not repaid, investors can become actual owners, too.)

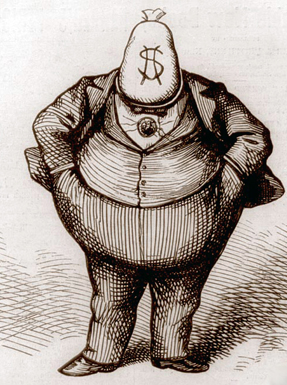

The antagonism toward

business owners making a profit is grounded, I am convinced, in

the notion that businessmen and businesswomen don’t really do

anything. They are not the ones assembling parts on the factory

floor, or manning the phones in the call centre, or cooking for

and waiting on rowdy customers in a bar. They just sit back and

rake in the surplus value created by their exploited employees,

to put it in Marxist terms.

The reality, though, is a

far cry from this caricature. Business owners are the ones who

organize all of the different factors of production according to

their best judgement of the demand for their products or

services and the supplies of sundry inputs. And it is their

accumulated wealth on the line if they misjudge any of these

elements. If this is truly worth nothing, then workers are free

to organize themselves and stop getting ripped off!

The situation is a little

different with large corporations where shareholders and

investors delegate their organizing duties to professional

managers. They are being paid solely for the risk they take with

their accumulated wealth. Anyone who objects to this in

principal, though, is basically objecting to the idea of earning

interest. But why should someone who delays his own enjoyment of

his wealth and risks losing it altogether not be

compensated? And just on a practical level, how much saving and

investment would occur if, in accordance with the ancient law of

Moses, it were forbidden to collect interest in return for

delaying one’s gratification and risking its loss?

There are people, though, who understand all of the above—who

think that it is both right and practical to reward owners,

managers, and investors for their work and trouble and risk—and

yet still feel funny about the idea of profiting from the

misery of others. Normal profit is okay with them, but

profiting from other people’s misery just feels wrong.

There is a sense, of

course, in which doctors and nurses profit from the misery of

others. They do so by receiving payment for their services, and

none but the most diehard socialist begrudges them this. But if

it is acceptable for doctors and nurses to benefit from the

misery of others through the earning of wages, why would it be

unacceptable for the owners of hospitals, insurance companies,

and pharmaceutical companies to benefit through the earning of

profits, or for investors and shareholders to benefit through

the earning of interest? For someone who understands the general

rationale behind profit and interest outlined in the previous

section, what reason is there to conclude that in this

case, they’re bad?

Perhaps the very phrase

“profiting from the misery of others” is to blame. It makes it

sound as if someone is gaining while someone else is losing. But

of course, this is not the case. Doctor and patient both gain

when patients get treated and doctors get paid. It’s a win-win

situation just as clearly as when I get milk from my grocer and

he gets paid. The owner of a hospital, then, benefits its

patients in the same way as the owner of a grocery store does.

We have another,

different phrase to describe the situation of someone gaining

and someone losing: it’s called profiting at the expense of

others. That is something worth condemning—and workers,

owners, and investors in such activities as grand larceny, for

instance, deserve our contempt. But alleviating suffering is a

valuable service. Not only those who provide the service, but

also those who organize the factors of production involved in

its delivery as well as those who lend their wealth to finance

it, deserve all the rewards they can earn from voluntary

participants in a free, competitive market. |